1975 – 1980:

ORIGINS & FOUNDING INSPIRATIONS

Establishment

The Rialto Youth Project was formally established in 1980. From the outset, it was formulated as something quite different to the traditional youth club model. Its appearance at that particular moment can be ascribed to two related developments. Firstly, the arrival of the community-based youth worker onto the youth work scene in Ireland. Secondly, the establishmnet of the Rialto Development Association (RDA) and its recognition that the needs of a significant sub-group of Rialto youth were not being met within the traditional youth club structure.

St Andrew’s Community Centre. Photo: Chris Maguire

Origins of the Community-Based Youth Worker

In the early 1970s youth work was almost entirely a voluntary effort dominated by the youth club model. In England they had developed youth services which tried to reach young people outside of those traditional youth clubs: the so called ‘unattached’. Maurice Ahearn was a key figure in the development of the idea of a youth work project driven by an impetus from the community. Coming from a background in social science, Maurice started in youth work in Crumlin in 1971, operating on the streets outside of the traditional club structure. By the close of the 1970s the figure of the community-based youth worker was established as s significant new feature. The origins of the community-based youth worker can be traced inpart to the establishment in Killkenny by Sr Stanislaus Kennedy of a Social Service Centre at community level. The centre there brought together a range of disciplines including social work, medicine, nursing and the community-based youth worker. It was the replication of that model of the Social Service Centre that Maurice encountered in Crumlin.

In those early days at the Crumlin centre Maurice worked with Larry Masterson, a co-founder of the Simon Community. Together they approached Comhairle le Las Oige with the idea of introducing a community-based youth worker to the centre at Crumlin. At that time Comhairle le Las Oige was working entirely with youth clubs, youth groups and scouts. Maurice was appointed as the Crumlin youth worker at a time when the role as such did not exist in Ireland, nor the training to become one. The job description was broad: get out into the streets and meet the unattached. Also, he was tasked to organise and engage with the local youth clubs in the area.

This was the beginning of the ‘detached youth worker’ at local level. Maurice quickly realised that he needed training. Following training in Glasgow with colleague Alan Murray, he became formally employed by Comhairle le Las Oige . Comhairle was divided internally on the question of the community-based youth worker. One of the big objections was the introduction of full time workers imto a field dominated by a voluntary service model. Nonetheless, in 1972 they agreed to proceed with the recruitment of 10 such youth workers in different areas of Dublin, one per area. Each community-based youth worker was responsible to the local parish unit. The selection of that first 10 was very much influenced by Maurice’s background in social science and community work.

After a couple of years of experience with the solo community youth worker it became clear that the job could not be done alone. A two person model was adopted. Crumlin became the first two person project and Rialto followed suit in the early 1980s. In terms of need, Rialto was immediately identified by Comhairle le Las Oige as a disadvantaged area and a priority for this new, experimental approach. At that point Fatima Mansions had become notorious as a black spot on the southside of the city.

Maurice Ahearn became manager of those 10 areas, adopting an open, experimental ethos where each locality could evolve according to their own needs and conditions. As one of that first generation, Noel Coughlan was assigned as community-based youth worker to Rialto. Based at the Parish Centre, St Andrew’s Road for two years , he concentrated on Fatima Mansions. Youth worker Christy Keely was next to take up that position in the late 1970s.

Rialto Development Association

In the case of Rialto, Comhairle le Las Oige made the initial approach to Sr Claude in her capacity as member of the Rialto Development Association (RDA) with a proposal for this new model of community-based youth worker. Rialto was perceived from the outset as different to the extent that the community youth worker initiative was supported by a strong Managememt Committee, itself a sub-committee of the RDA. It was that sense of strong governance that gave the Rialto project greater autonomy and self-direction in those formative years compared to other regions where the model was introduced.

When Tony MacCárthaigh was assigned to Rialto in 1975 his experiences in South America with community activism had already convinced him of the primacy of community. One of four priests in the parish, each with their own designated patch, he began working with the community of Dolphin House. Initially involved with the Dolphin House tenants association, after six months a vacancy arose in Fatima Mansions and he took up duties there.

In Fatima he became immersed in community issues. There was a small community centre and the issues of the day concerned the general state of the place: sewage problems, unemployment and problems with robbing and stealing, which in retrospect might be seen as somewhat ‘innocent’ in the light of what was to follow later.

By the mid to late 70s the care managers system at Fatima Mansions was breaking down in a climate of disinvestment but there was still a great sense of community and networking in Fatima. From a parish perspective, that sense of community within Fatima was in contrast to a larger sense of disconnect between communities in Rialto. In New Island Road in the heart of Rialto there was a solid community involved in all the parish activities. Rialto Street and Rialto Buildings were identified with the old Rialto residents, also heavily involved in parish matters. Fatima Mansions and Dolphin House were far less involved with church.

In terms of outlets for young people, Rialto Street and Rialto Buildings were associated to a large extent with the Ferrini Youth Project, a traditional club run by St Vincent De Paul volunteers. At the time, the Ferrini Club had an outreach into Fatima and Dolphin. Young people from different parts of Rialto encountered each other there. However, from a macro-community perspective there was an obvious divide between communities. It was that basic observation that motivated Tony MacCárthaigh to bring people around the table to start some sort of a coordinated approach.

The foundational roots of the Rialto Development Association (RDA) can be located in 1975 with a community sports day held in the Dolphin House football field. The day was organised and driven by young people from Ferrini, themselves living in Fatima, Dolphin and the general Rialto area. Featuring football and various games, it was the first effort to bring together people from the different areas and had a major youth focus. The sports day coincided with the first steps towards the setting up of the RDA. It was a catalyst, creating the impetus to make connections with different parts of the community, to bridge that disconnect. The RDA was also more broadly concerned with developing the area socially and culturally.

Other founding figures of the RDA included Peter Kenny, Bobby Charleton, May O’Donohue and Tony Carroll, some of whom are still involved. Founding members also included the late Sheila McGuiness and Jim Roche. Jim was centrally involved with a particular interest in engaging young people with the inner city games. In those early days it was a question of formulating an approach. The sports day was followed by an immediate emphasis on fund raising with a view to establishing a base in the community.

The sports day developed into a community week. In those establishment years community week was a key feature, encompassing a variety of activities: ladies football, football tournaments and a big social night at the end of the week. The focus was on the idea of building community. A community Co-Op was also developed. Produce was purchased early at the Saturday morning markets and sold locally in a cul de sac in Rialto Cottages and later, at the Parish Centre.

The RDA started out as a community development initiative in the broadest terms with a strong focus on young people. It also wanted to establish a base: there was a dearth of community resources in Rialto at that time. It had strong links with Dublin City Council. RDA meetings were attended by Fergus Lynch, Community Development Officer with DCC. Early on in its development the RDA became a limited company, working with DCC on key goals such as establishing a base and funding. It therefore required Articles of Association. It was a matter of firming up its sense of governance.

When Noel Coughlan became the youth worker for Rialto by appointment of Comhairle Le Leas Oige, he had a brief to outreach young people. While there was no formal relation between his outreach work and the RDA, there was nonetheless an informal link that was very much part of the ground work that led to the setting up of the Rialto Youth Project. In the late 1970s the RDA was encouraged to make an application to CDYSB seeking to establish the Rialto Youth Project. A Management Committee was established as a sub-group of the RDA to oversee the work of the new youth project.

S Block, Fatima Mansions. Photo: Chris Maguire

Context Markers for Rialto

In addition to those two structural elements described above, the impetus for establishing the Rialto Youth Project arose from a number of key context markers. Firstly, the establishment of the Rialto Youth Project was in no small way connected to a broadcast in 1979 by the RTE current affairs programme Seven Days of a special feature on Fatima Mansions. The feature focused on how people living in Fatima Mansions could no longer leave their keys in the door. Over 1978 and ’79 drugs had entered the scene in Dublin’s innercity. As drug addiction became an ever increasing feature among the flat complexes of Fatima Mansions, the trust element went out in the local community. The Seven Days feature focused on that breakdown of trust. A clear message was sent out by the residents of Fatima Mansions: ‘I can’t trust my neighbours – I can’t leave my keys in the door’.

Secondly, while Rialto at that time had well established youth clubs such as St. Vincent De Paul’s Ferrini Youth Club and the Peace Corps., there was acknowledgement at the time of a constituency of young people that were not engaging with those options. In the RDA they were identified as ‘unclubbable’ young people. The origins of Rialto Youth Project lie very much in the comittment to create a youth work response to the needs of those young people.

Thirdly, unemployment among young people in Ireland at that time had reached record levels. While young people in Rialto were subject to multiple disadvantages arising from structural inequalities, the level of unemployment among the young people of Rialto in 1979 was disproportionatly high.

Fourthly, the deteriorating situation in Northern Ireland was an important context marker. There was a sense within the RDA that the combination of those factors outlined above rendered a significant group of young people vulnerable to recruitment by republican interests operating in the community at the time.

Educational disadvantage has been a key focus from the outset. When the Rialto Youth Project started in the 1980s, early school leaving was a big issue. In its start up phase interventions were very deliberately aimed at getting young people to stay in school to sit their Junior Certificate.

1980 – 1983: Early days

As we have seen, the Rialto Youth Project was not established in a vacuum. In 1980 there was a variety of already established youth clubs and other initiatives. At the time, those initiatives included the Ferrini Boys Club, the Peace Corps, the Scouts, the Rialto Variety Club and the Rialto Sports Council. Ferrini had been in Rialto for 50 years. When the RDA applied for the funding to establish the Rialto Youth Project many of the founding group were also involved in Ferrini. The Rialto Sports Council were chiefly concerned with the lack of participation by young people from the inner city in the Community Games.

Two Youth Workers

It was a question then of establishing a distinct and separate role for the project within that competing field of provision. By November 1981 the Rialto Youth Project had established positions for two youth workers: Christy Keely and Jim Lawlor. In the division of labour Christy Keely was engaged in face-to-face work with a small number of families in severe difficulltyin Fatima Mansions. Christy adopted a social care / social work model while Jim was coming from a voluntary youth work perspective. At that time Fatima Mansions had become notorious in relation to problems with drugs.

The other position, held by Jim Lawlor, was originally envisaged as one of support for those already existing youth initiatives in Rialto. However, it became immediately evident that those organisations considered themselves self-sufficient to varying degrees, without need of assistance from the new youth project. There was an opportunity therefore to re-define that position working in conjunction with a strong tenants group in Dolphin House.

Early Work in Dolphin House

Initially there were meetings every Monday night in Dolphin House with an emphasis on creating a shift in thinking from tenants émeetings to community development. That shift was formulated by the idea of establishing a Dolphin House Development Association. At one of those meetings a mother requested support for finding her daughter who had absconded to England with a local drug user. Through that support work Jim Lawlor encountered and established connections with other mothers in Dolphin House. In the course of discussion with those mothers it was agreed to formalise the process into a personal development session. The women started coming over to St. Andrew’s once a week for a personal development course which continued for 18 months on Wednesday nights.

That way of working with the women eventually led to more direct youth work in Dolphin. The women shared concerns and also embarrassment about taking on sex education with their children. Jim Lawlor agreed to take on that role and began working directly with the young people.

Disaffected Youth

There were also early engagements with young people in Rialto beyond Dolphin House and Fatima Mansions. The RDA had received complaints about a group of young people hanging about the New Ireland Road and Cross Road. The youth project was asked to do something. Drawing on previous experience with friendship programmes Jim Lawlor invited those young people, who were disaffected from the Ferrini Youth Club, to engage in a friendship module. That initiative was the first attempt to work with young people from Rialto outside of the flat complexes in Fatima and Dolphin.

As Jim Lawlor’s role evolved the Management Committee decided there was too much emphasis on community development and that the focus should be more on youth work. With that switch in emphasis the Dolphin youth work role came more in line with the work in Fatima.

St. Andrew’s Boardroom

In that early phase of establishing the project it was based on St. Anthony’s Road at the Parish Centre. The present site at St. Andrew’s Community Centre on the South Circular Road was a derelict building. The RDA had renovated one of the rooms there for use as their board room and met there on a monthly basis. When the two youth workers secured use of the board room they began to use it as a base for meeting and interacting with young people. As Christy and Jim began to encounter young people arriving at the project door they were increasingly confronted with the problems of drug addiction. This was a major challenge beyond their respective youth work experience.

From Crisis Intervention to Campaigning

In those first three years, much of the work was crisis intervention. Such an approach proved unsatisfactory. There was simply too much going on. In the effort to establish a neighbourhood youth project for Rialto the organisation was responding on all fronts in relation to drugs, sex education, community development and so on. Young people were presenting with all sorts of dire needs. Essentially, those first few years were a process of needs assessment. Through that process the gaps were recognised and rather than attempting to meet all those gaps, the Rialto Youth Project became a campaigning organisation. It turned its attention to campaigning for the services needed in the community to meet the needs of its young people. It turned its attention in particular to the problems of drug addiction.

1984 – 1995: CAMPAIGNING ON DRUGS

Unusually, the Rialto Youth Project started out with funding for three years (1980 – 1983). At the conclusion of that first three year phase the schedule changed. An evaluation was carried out by Chomhairle Leas Oige. While their report was overwhelmingly positive the funding schedule was changed from then onwards from the three year cycle to annual funding.

The end of the three year funding cycle was accompanied by changes in the composition of the Management Committee. Two new people, Michael O’Connell and his wife Mary, joined the Management Committee. They came from the CYC model and their influence corresponded with the departure of Christy Keely after some four years of service to the project.

In 1984 Joe Donohue became involved with Rialto Youth Project when the Ferrini Youth Club agreed to the project running a drop in centre at St. Andrew’s. Joe was given the job of running the centre under a social employment scheme. The initiative was used for the most part by young people from Fatima Mansions.

Discarded needle, Fatima Mansions. Photo: Chris Maguire

Concerned Parents Against Drugs

By 1984 the drug issue was dominating and young people were at the heart of it. A meeting was held in the hall in St. Andrew’s Community Centre to launch a report on the first three years of the Dolphin Community Development Association. With Jim Lawlor chairing, the meeting was overtaken by an incident earlier that day in which a child had come upon an abandoned syringe and pricked himself with it. With a small number expected, the meeting was attended by about 200 people.

The incident with the child and the syringe and the night of that meeting could serve as a marker for the formation of Concerned Parents Against Drugs (CPAD). CPAD was comprised mostly of women. They sat outside the blocks in Dolphin and Fatima and told any approaching drug dealer to go away. The dealers were told that there would be no-one buying or selling drugs on their block. When the women prevented the drug dealers from dealing they started to arrive with guns. They drove into the flats with the gun visibly protruding from the car window. At that point the men got involved.

In terms of youth work the focus shifted towards advocacy work with young people. This took the form of negotiations between young people, the CPAD and the Gardai and their Juvenile Liaison Officers. The young people were complaining about harassment and beatings by the CPAD. In some sessions young people were facilitated to confront the CPAD directly.

Campaign for Drug Services

In the late 1980s a residential planning weekend with Rialto Youth Project staff and members of the Management Committee proved crucial in the switch from crisis intervention towards a focus on campaigning for services. During the weekend a workshop facilitated by John O’Connell of NUI Maynooth proved to be particularily significant. Taking a social analysis approach, the workshop changed views on how the organisation should work. It was decided that Jim Lawlor would dedicate 5 % of his time to campaigning. Tony MacCárthaigh was in attendance as a member of the Management Committee. He argued convincingly that the drugs issue was central: everyone is affected by drugs. The absence of any service for drugs was identified and the decision was made that the RYP would start its campaigning approach on the drugs issue.

Methadone V Community Drugs Team

The Rialto Youth Project’s first campaign was to get drug services for the area. The campaign started by engaging with other drug projects such as Anna Liffey, Coolmine and Jervis Street. In the Health Board at the time Dr Joe Barry had responsibility for drug addiction. At consultation meetings with Dr. Barry assistance was requested in helping the youth project work out how best to respond to the drug problem. He was the key person responsible for setting up drug teams. Ballymun and Rialto were the first areas targeted. The debate on methadone was central at that time and Dr. Barry envisaged Rialto as a drug centre for methadone treatment. Following frank discussions between Jim Lawlor, Gráinne Lord and Dr. Joe Barry it was agreed that a Community Drugs Team would be established instead of the methadone distribution model.

New Influences

In addition to the turn towards campaigning, the second half of the 80s saw some new figures join RYP that would have an enduring influence. In 1985 a Team Work Scheme for 20 young people brought new youth workers such as Gloria Kirwan into the project. Youth unemployment and drug addiction were key issues at a local level. The years 1987 to ‘89 saw the emergence of the summer projects, the first summer school at Lough Dan and new leaders establishing their influence.

Blackwell Spelling Kit

Through arrangements with NUI Maynooth students came on placement to Rialto Youth Project. One of those students, Michael McDonagh, introduced the project to his Blackwell Spelling Kit. While many young people would not concede to having a literacy problem, most would acknowledge a spelling problem. Responding to its popularity, the project acquired its own spelling kit. Joe Donohue became expert in using the spelling kit as a teaching device. The resulting spelling programme became an established education and literacy campaign with huge levels of participation and excitement for three years. In 1988 John Bissett returned from Austrailia and built on the work on spelling with young people to introduce a focus on writing.

Creativity in Youth Work

At that time Niall O’Baoill of Wet Paint had established visual arts projects in several communities and was instrumental in bringing artist Liz McMahon to work with Rialto Youth Project. The first visual arts collaboration between Rialto Youth Project and Niall O’Baoill’s Wet Paint involved making a tableau of a famous Renoir painting.

In 1989 Gráinne Lord joined the organisation, bringing a strong focus on creativity in youth work. In music, as part of a drama production, she was the first to introduce keyboard lessons. In visual arts her Renoir project with visual artist Liz McMahon worked with young women. Together they re-staged a famous Renoir painting using the women as models.

Rialto Area Action Plan. Photo: Chris Maguire

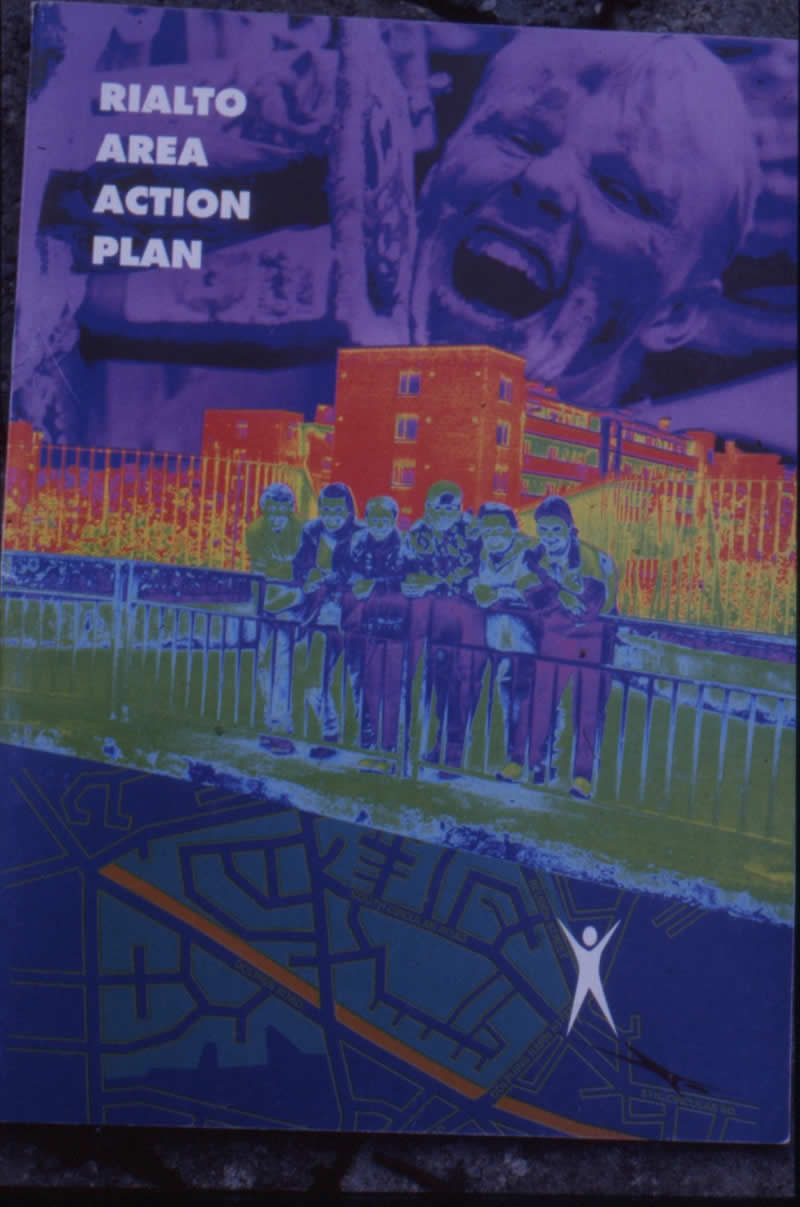

Rialto Area Action Plan

In the mid-nineties a Rialto Area Action Plan was funded by Area Development Management (ADM). A grant of 30,000 (Irish Punts) was entrusted to the Rialto Development Association as the local agency with an established track record in community development. This initiative led to the establishment of the Rialto Community Network, followed soon after by the establishment of the Canals Communities Partnership. With a remit covering Bluebell, Inchicore and Rialto, the Canals Communities Partnership was the last and smallest partnership company of its kind to be set up. In the early days of the Partnership youth work was an active part of the agenda.

1985 – 1995: DRAMA & ISSUE-BASED YOUTH WORK

Those first ventures into the visual arts also saw the introduction of drama as a powerful way of working with young people. The origins of that engagement with drama developed from a number of directions.Youth worker Joe Donohue took a big interest in drama, and in particular, the productions of Dublin-based Passion Machine. He started to bring groups of young people to see their plays at the SFX.

For Jim Lawlor, the connection with drama came out of contact with Niall O’Baoill and his work with Wet Paint. Wet Paint were trying to bring drama to young people. They had developed a play called Tangles about a gay man. The play was set up in a way that invited groups of young people to see aspects of the work and engage with it. Jim Lawlor was interested in the process and began working with Niall to explore the possibilities of working through drama with young people in their own community.

Requiem for Julie

The first RYP production, Requiem for Julie was a play about drugs. Written by a teacher and friend of Gráinne Lord’s, it had already been performed at his school. At St. Andrew’s a group of young people were shown a video recording of Requiem for Julie and responded really positively. Permission was granted from the author to make the play more local, more applicable to life in Rialto.

Paradise Island

Emboldened by Julie, the next production called Paradise Island, was a first attempt at something more homegrown. The play was written through a workshop process. To facilitate that process Niall O’Baoill of Wet Paint brought in Nico Brown and his partner. Jim Lawlor and John Bissett featured in the play as tropical birds, swooping dramatically across the stage.

A Trilogy of Plays

The relationship with Niall O’Baoill at Wet Paint was consolidated and Rialto Youth Project went on to produce a trilogy of plays that spanned up to 1995. Niall O’Baoill coordinated production and introduced Kathy McCardle. That trilogy was issue-based. Each play cycle took a year to complete from the very first meeting, building the interest, the writing process and the performance to the sign-off on the evaluation.

The first, produced in the late 1980s was called Here Today, Where Tomorrow? and dealt with the issue of unemployment. The second play, produced in the early 1990s, was called In the System and was themed around the Aids crisis. The third one in that series, produced in the mid-90s, was called Inside Out and dealt with the prison system. A video documentary about the making of Inside Out was also produced.

1995 – 2004: REGENERATION CAMPAIGNING

Joe Donohue and Tony MacCárthaigh were both key figures in the setting up of Fatima Groups United (FGU). As a resident representative association, FGU replaced the Fatima Development Group which was dominated by one family in the Fatima Mansions flat complex. Joe’s work in Fatima with the young people ensured high visibility for the Rialto Youth Project. In 1999, having rapidly established a profile in Fatima, Joe Donohue was appointed chairperson of FGU.

In November 1999 formal negotiations commenced between Dublin City Council and Fatima Groups United on the regeneration of Fatima Mansions. Sheila Norden was given the mediation role between DCC and FGU. Following a particularly difficult session during that early mediation process, in consultation with Jim Lawlor and Niall O’Baoill, Joe decided to call a moratorium on negotiations. The moratorium was succesfully negotiated, opening up a process for creating a community-led vision for regeneration.

From Drama into the Street

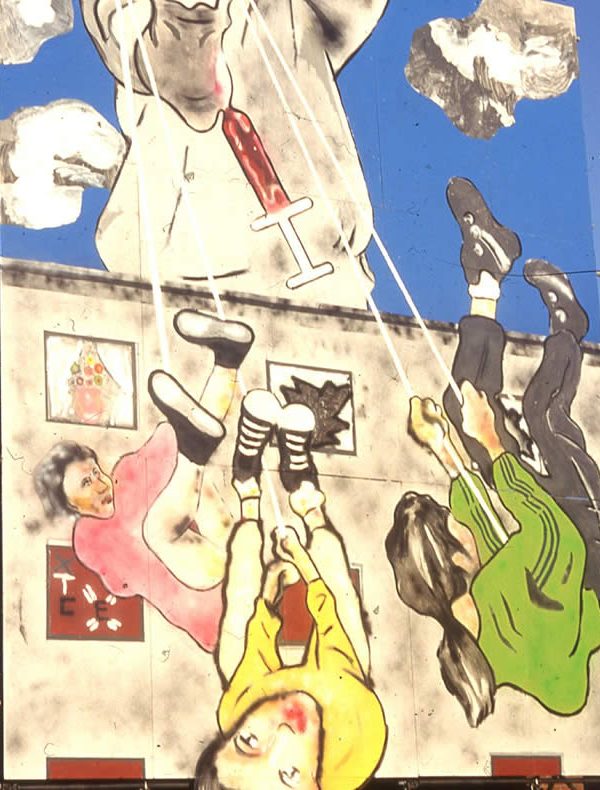

In terms of the arts and issue-based youth work, the community struggle for ownership of the regeneration process in Fatima was accompanied by a shift from drama to the theatre of the street.

The trilogy of issue-driven plays concluded in 1995 with Inside Out. The youth project’s first major involvement in street performance was in collaboration with a street theatre group from Barcelona called El Comediens. They had a concept for the St. Patrick’s Day parade which involved Rialto, Ballymun, Pearse Street and a community group in Coolock. Each area was themed on one of the elements: fire, wind, water and air. Rialto was fire. It was a large-scale, citywide operation. In Rialto, El Comediens had a good way of working, successfully engaging 30 young people on roller blades. With Padraig Breathnach from Macnas as event Director, each element came from different parts of the city and converged in the centre.

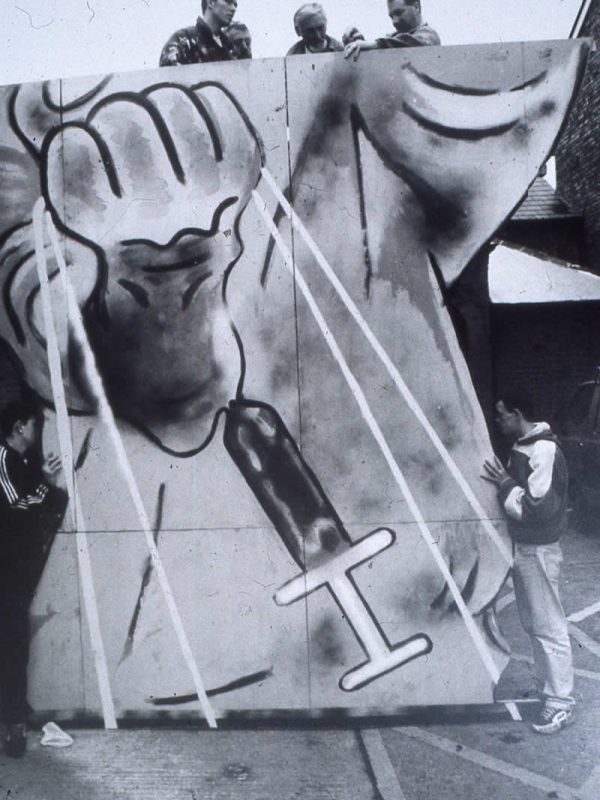

Burning the Demons, Embracing the Future

Following the El Comediens collaboration the Rialto Youth Project leadership convened a planning weekend at Invern, Galway. The Network Drugs Team also participated along with local artist Chris Maguire. The Burning the Demons, Embracing the Future event was a big moment for the youth project and its origins can be traced back to that planning weekend at which Charlie O’Neill proposed the notion of a photo realist project with a number of phases.

Coordinated by Chris Maguire from the outset, young people were given cameras and sent out to take pictures of what it’s like to live in Rialto. Using St. Andrew’s as a base, the resulting photographs were laid out and with facilitation by Charlie O’Neill, the 10 most representative images were chosen. A further session at Charlie’s studio at Public Communications Centre (PCC) honed it down to a defining, composit image.

In the next phase of the process, Chris Maguire worked with the local young people engaged with the project to make a mural based on the image. When the mural was finished in September it was mounted on the building in St. Andrew’s. Its appearance there changed the process from a youth project to a community development project. Middle class residents responded negatively to the mural as a defining image of Rialto. In response, Niall O’Baoill produced an explanatory leaflet on the project which was distributed to every household in Rialto.

It was only at that later phase of the project that the symbolism of burning the mural came into focus. Breakfast meetings were organised to inform the community about the project and the idea of a public, parade event around burning the mural. In response a group of local women presented 75 pounds collected to support the project. It was evolving into more of a parade event.

The Burning the Demons, Embracing the Future event became a very significant moment. While the process had started in late September, by October young people had not yet fully bought in: they were gathering wood for the Halloween bonfire. A group of men, including youth worker Paul O’Shaughnessy and volunteer John Bissett volunteered to be on site with screw guns to stack the pallets for the fire sculpture. A pyrotechnics man known locally as Seamus The Firestarter directed how the bonfire was to be built. Youth workers realised that the Rialto Majorettes and other groups were coming to join the parade. The site at St. Andrew’s became a frenetic scene of construction.

Starting out with an expectation of an event engaging about 20 young people, the parade that night was joined by about 2,000 local people congregated at the dry canal site where the sculpture was burned. The Gardai were very complimentary. They were impressed with the Rialto Youth Project’s level of organisation with Dublin City Council and with the Gardai themselves. For the Rialto Youth Project it was a moment of realisation: we had a capacity to organise that was far greater than we thought.

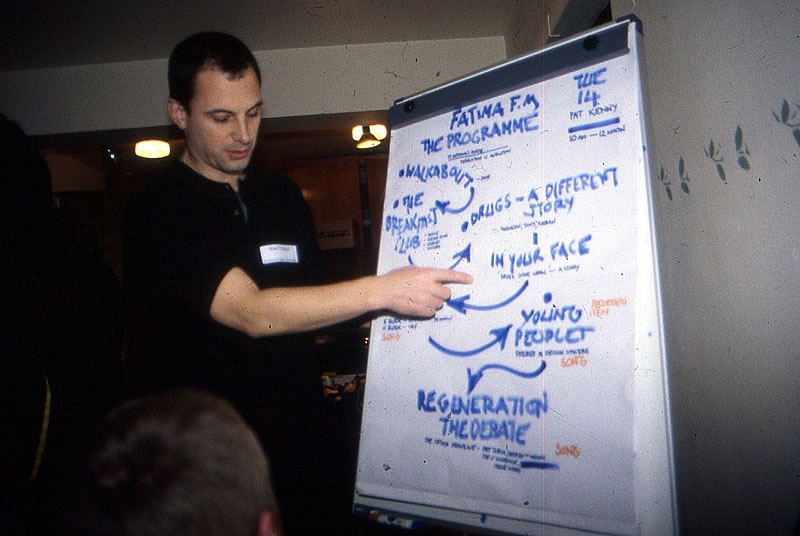

Niall O’Baoill and planning details for the Pat Kenny radio broadcast at Fatima Mansions. Photo: Chris Maguire

The FAST Team and the Festival

The FAST Team was established in 2000 as a key strategy group for the negotiations with Dublin City Council on regeneration for Fatima. As a member of the FAST Team, Rialto Youth Project Manager Jim Lawlor brought the youth project’s perspective, resources and advocacy to the table. Other members included Joe Donohue from Fatima Groups United, Charlie O’Neill from PCC and Niall O’Baoill, Cultural Coordinator at FGU.

With Burning the Demons as an inspiration, the regeneration process for Fatima Mansions was accompanied by a series of community-led festival events. It was through that FAST Team collective process, meeting on Thursday mornings, that the festivals became key to mobilising the community. There was a strong realisation that the regeneration process could be supported and given community expression at key moments through the festival.

Through engagement with festivals, the Rialto Youth Project developed a vital role of stewardship over community-based arts processes in the public space. Also, the festival was key in linking the regeneration process to public space. In addition, the festivals were not just a way of bringing people in and engaging them. They also functioned as a way to communicate a message to DCC: we are organised, we are involved and local people are involved.

In youth work it afforded opportunities to engage certain individuals considered beyond the reach of youth work. Festivals frequently required the hiring of expensive equipment. At such times those figures in the community who were considered most likely to steal such equipment were given sole responsibility for its safety in a very public way. The strategy was highly effective.

Eleven Acres Ten Steps

Following the moratorium on negotiations with DCC the community set about developing their own vision for regeneration of their area. That vision was contained in Eleven Acres Ten Steps, a publication outlining the process and the vision for community regeneration. Working with the FAST Team, Jim Lawlor had a key role in gaining the community endorsement of that vision. At a gathering with over 35 local people Jim presented a detailed overview of each principle within the document, ensuring that each was understood and agreed to over the course of an evening consultation at St. Andrew’s Community Centre.

Demolition of The Arch, Fatima Mansions (June 13th, 2006). Photo: Chris Maguire

2004 – COLLABORATION, CONSOLIDATION

Jim Lawlor & Paul Hendrick, St Andrew’s Community Centre. Photo: Chris Maguire

In 2004 there were a series of changes in personnel that, taken together, mark out the year as a key time of transformation, the beginning of the modern era. That year youth workers Gillian O’Connor, Nichola Mooney and Sabryna Porter joined RYP along with Linda Evans and Paul Hendrick. Artist Fiona Whelan also took up residency at Studio 468, initiating a long term collaborative relationship with the youth project.

Fatima and Dolphin Homework Clubs

It was also a time of organisational growth. The Local Drugs Task Force (LDTF) was established and Manager Jim Lawlor was nominated from the LDTF to the Youth Services. Jim was appointed to their development group with two others. The group was tasked with looking at the needs of young people and the development of services for young people in the Canals Communities area. They fought for youth provision service positions in each of the three areas. David Treacy of CDYSB allocated funding for a youth worker for Dolphin Homework Club on condition that it was an RYP post. Sabryna Porter was appointed to that position. At the same time, Rialto Youth Project were beginning to collaborate with Fatima Homework Club.

Arts-Based Youth Work

In the summer of2005 the Rialto Youth Project was involved in a series of major art projects including Tower Songs, the Mechanical Sculpture, the Caged Woman and a mural at the LUAS. There was also an important shift in the thinking around arts-based youth work, Niall O’Baoill encouraged individual youth workers to follow their personal creative interests. It was a time of intensive collaboration and discussion. The need to put a structure on arts-based youth work was recognised. Niall started that process, always with an eye to the bigger vision.

Rialto Learning Community

It was also around this time that the possibilities of The Atlantic Philanthrophies funding came into play. That funding opportunity was organised around the concept of the Rialto Learning Community (RLC). A key requirement for the RLC concept was that every project in Rialto had to come together. Michael Little from Dartington University specified as a condition of funding that there had to be agreement among Rialto-based community development projects and local people. The RLC had a basic research question: is the work we’re doing valuable or not?

It was never envisaged at the outset, in the development of the RLC concept, that the Rialto Youth Project would be the funding recipients. There was an insistance among the project convenors that there would be agreement on what age group the RLC would work with, and furthermore. that it should be 11 to 14 year olds.

The group involved in the subsequent formation of the RLC comprised of Jim Lawlor RYP, Joe Donohue FGU, Niall O’Baoill FGU and John Whyte from the Regeneration Board. Liam O’Dwyer from the IYF had an interest and brought in consultant Billie Murphy. Building on previous work with Youth Reach, Billie Murphy introduced the idea of Individual Learning Plans (ILPs).

Arcade Project

More recently, the RYP has turned its attention to the question of capturing its own model of practice and sharing its approach in the broader field of youth work. RYP is a very particular kind of organisation. The Arcade Project (2011 – 2016) in collaboration with Vagabond Reviews has been an important part of the work of capturing and describing that distinct approach to youth work. Through the Arcade process the organisation is moving towards presenting a coherent, communicable model of practice.